A curious experience

Plus: Angela Merkel - sleepwalker? The Crimea question. Putin - war criminal & Xi's gracious host

History of the Present (fortnight to 18 March 2023)

German Bundestag debates what I really said. (Might I be permitted to add a word…?)

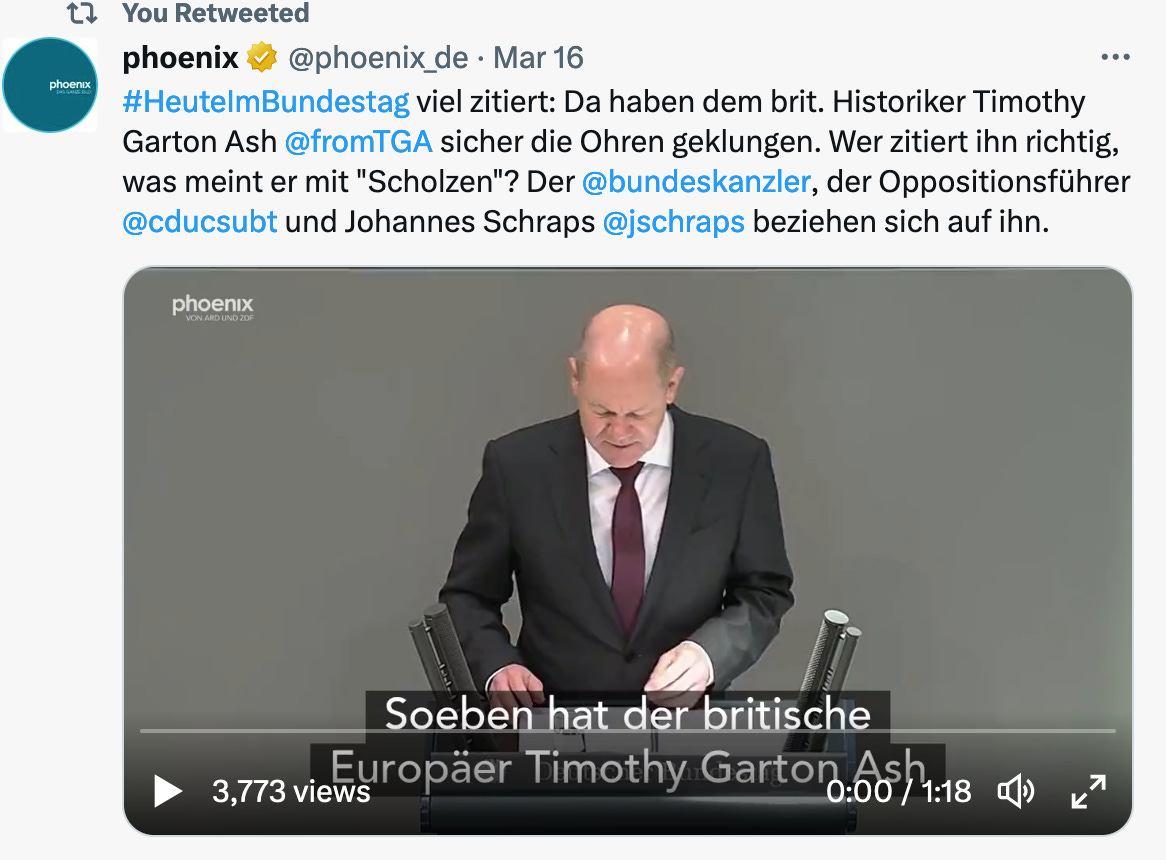

Last Thursday (16 March) I had the curious experience of watching the German parliament debate what I had really said. Chancellor Olaf Scholz opened his statement in advance of the next European Council meeting in Brussel…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to History of the Present to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.